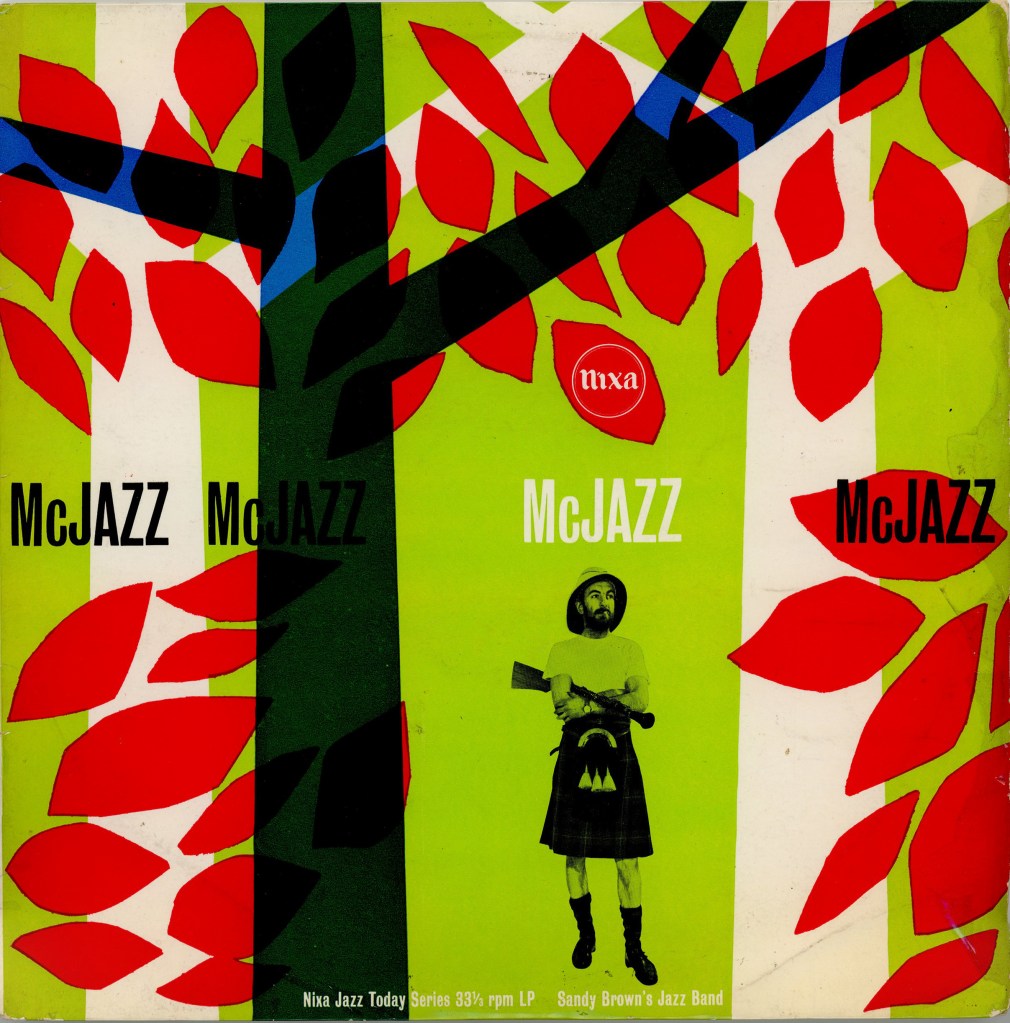

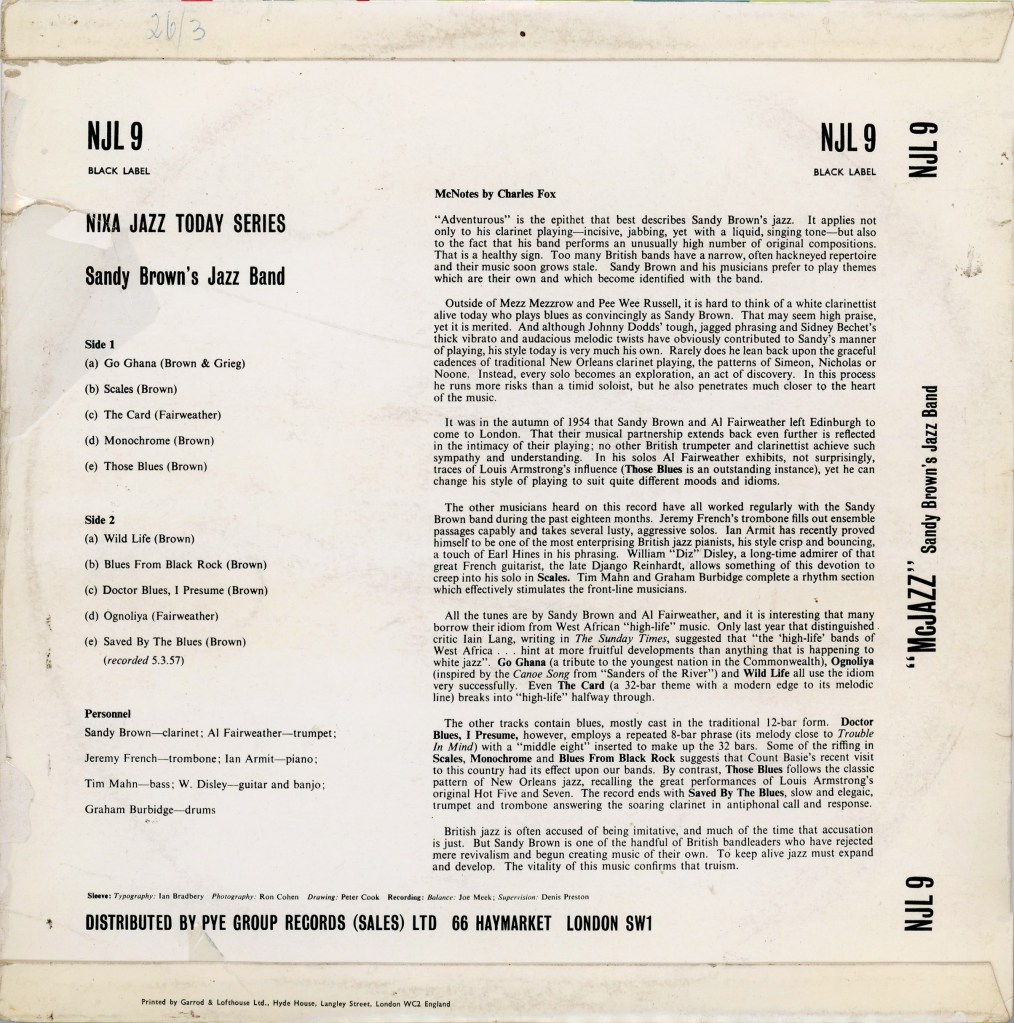

Pye Nixa NJL 9

Nixa jazz Today Series

12” LP

Recorded 5/3/57

Tracks

Side 1

(a) Go Ghana (Brown & Grieg)

(b) Scales (Brown)

(c) The Card (Fairweather)

(d) Monochrome (Brown)

(e) Those Blues (Brown)

Side 2

(a) Wild Life (Brown)

(b) Blues From Black Rock (Brown)

(c) Doctor Blues, I Presume (Brown)

(d) Ognoliya (Fairweather)

(e) Saved By The Blues (Brown)

Sleeve Notes

McNotes by Charles Fox

“Adventurous” is the epithet that best describes Sandy Brown’s jazz. It applies not only to his clarinet playing – incisive, jabbing, yet with a liquid, singing tone – but also to the fact that his band performs an unusually high number of original compositions. That is a healthy sign. Too many British bands have a narrow, often hackneyed repertoire and their music soon grows stale. Sandy Brown and his musicians prefer to play themes which are their own and which become identified with the band.

Outside of Mexx Mezzrow and Pee Wee Russell, it is hard to think of a white clarinettist alive today who plays blues as convincingly as Sandy Brown. That may seem high praise, yet it is merited. And although Johnny Dodds’ tough, jagged phrasing and Sidney Bechet’s thick vibrato and audacious melodic twists have obviously contributed to Sandy’s manner of playing, his style today is very much his own. Rarely does he lean back upon the graceful cadences of traditional New Orleans clarinet playing, the patterns of Simeon, Nicholas or Noone. Instead, every solo becomes an exploration, an act of discovery. In this process he runs more risks than a timid soloist, but he also penetrates much closer to the heart of the music.

It was in the autumn of 1954 that Sandy Brown and Al Fairweather left Edinburgh to come to London. That their musical partnership extends back even further is reflected in the intimacy of their playing; no other British trumpeter and clarinettist achieve such sympathy and understanding. In his solos Al Fairweather exhibits, not surprisingly, traces of Louis Armstrong’s influence (Those Blues is an outstanding instance), yet he can change his style of playing to suit quite different moods and idioms.

The other musicians heard on this record have all worked regularly with the Sandy Brown band during the past eighteen months. Jeremy French’s trombone fills out ensemble passages capably and takes several lusty, aggressive solos. Ian Armit has recently proved himself to be one of the most enterprising British jazz pianists, his style crisp and bouncing, a touch of Earl Hines in his phrasing. William “Diz” Disley, a long-time admirer of that great French guitarist, the late Django Reinhardt, allows something of this devotion to creep into his solo in Scales. Tim Mahn and Graham Burbidge complete a rhythm section which effectively stimulates the front-line musicians.

All the tunes are by Sandy Brown and Al Fairweather, and it is interesting that many borrow their idiom from West African “high-life” music. Only last year that distinguished critic lain Lang, writing in The Sunday Times, suggested that “the ‘high-life’ bands of West Africa hint at more fruitful developments than anything that is happening to white jazz”. Go Ghana (a tribute to the youngest nation in the Commonwealth), Ognoliya (inspired by the Canoe Song from “Sanders of the River”) and Wild Life all use the idiom very successfully. Even The Card (a 32-bar theme with a modern edge to its melodic line) breaks into “high-life” halfway through.

The other tracks contain blues, mostly cast in the traditional 12-bar form. Doctor Blues, I Presume, however, employs a repeated 8-bar phrase (its melody close to Trouble In Mind) with a “middle eight” inserted to make up the 32 bars. Some of the riffing in Scales, Monochrome and Blues From Black Rock suggests that Count Basie’s recent visit to this country had its effect upon our bands. By contrast, Those Blues follows the classic pattern of New Orleans jazz, recalling the great performances of Louis Armstrong’s original Hot Five and Seven. The record ends with Saved By The Blues, slow and elegaic, trumpet and trombone answering the soaring clarinet in antiphonal call and response.

British jazz is often accused of being imitative, and much of the time that accusation is just. But Sandy Brown is one of the handful of British bandleaders who have rejected mere revivalism and begun creating music of their own. To keep alive jazz must expand and develop. The vitality of this music confirms that truism.

Personnel

Sandy Brown-clarinet; Al Fairweather-trumpet:

Jeremy French-trombone: lan Armit- piano:

Tim Mahn-bass; W. Disley-guitar and banjo:

Graham Burbidge-drums

Sleeve:

Design: Ian Bradbery

Photography: Ron Cohen

Drawing: Peter Cook

Recording:

Balance: Joe Meek

Supervision: Denis Preston